“At this point, why photograph at all?”

It was a good question–a great question—even outside the context of the current conversation.

I was speaking to a friend who was frustrated with the rise and adoption of generative AI (artificial intelligence).

“Instead of reducing monotony in work, it is being used to savage the arts!” they continued.

“While it’s true that society is exploring the use of AI and that it will be adopted in one way or another, I have hope that creatives and brands will push back and will hold fast to creative built on the back of actual human experience rather than something feigning it, even if very well. At some point, we will have to decide our principles and where we will draw the line. Let’s see where things settle in the next couple of years.”

I could see the larger psychological, economic, and creative implications that my friend was so afraid of. But their initial exclamation stuck with me even after I arrived home–

“Why photograph at all?”

To get rich, of course!

I began to think of some of the possible reasons.

“Well, because I like it,” I thought.

Although this answer is true, it was a bit too lazy and too childish a reason to spend 15 years of time, effort, energy, and suffering associated with the choice to make photographs. I enjoy many things that are bad for me or pointless outside of self-gratification. I was looking for an answer with sense, with reasoning.

I’ve heard cliches over the years, like “to speak truth to power,” “redefine a people or an idea,” or “shine a light on the darkness of the world.”

I can’t help but feel that many of these responses come from an inflated sense of self-importance–a savior/hero complex that doesn’t match reality.

That light we are shining has become incredibly bright over the years, especially with the saturation of the photography industry and social media. In its attempt to arouse feelings of empathy, the bombardment of tragic images from around the world has numbed the collective viewer's conscience, making it feel more familiar and inevitable. Photography, in a sense, is a snake that has eaten its own tail. This begs the question, does the photography industry have a responsibility to protect and ensure its impact, even from itself? How?

As far as speaking truth to power is concerned, very few images claw their way through the billions of other images to sit in front of power, and even fewer cause that power to care. While it’s a romantic sentiment I would welcome should it happen, speaking truth to power is not why I photograph. Lastly, I certainly don’t have aspirations for or assume I have the right to speak for or redefine how an entire group of people with nuanced opinions and perspectives is viewed, even if I’m a part of said group. Besides, the idea of my images being widespread enough to change even a fraction of society's opinions about them is silly. Even if I just want to change one person's opinion about a group or idea, what kind of arrogance makes me think that I, out of everyone else, should have the right to do so?

To document history?

Photography plays a critical role in reflecting on history and understanding the present. Even so, it requires much context and active preservation by current and future generations.

Usually, this preservation by future generations happens only for major historical events. Are you somewhere where almost no other photographer has access and earth-changing history is frequently made? Likely not.

While it’s possible for a photograph to defeat time, it is usually defeated.

There are over 7.9 billion people on this earth, many of which have cameras. Even if you find yourself, once in a while, at an important historical event, what are the odds that it will be significant enough to be reviewed in the future and that the photos shown will be yours?

And what if they are? Is that why you take pictures–for that chance? Again, this is a fine idea, but it doesn’t explain why I grab my camera every day.

What about for legacy?

Whatever that means. If you’re one of the most famous figures in history, your name might be known for a few additional generations. Still, more than likely, you’re going to die, and your images will be forgotten after a single generation. Even when families use photography to make a portrait chronicle of themselves (much less images each family member makes), are those family photographs hanging on the walls of future generations? How many of those people even know the names of their great-grandparents?

Suppose you die, are an outstanding photographer, and your family has means. In that case, they might set up a foundation in your name or show some of your images in exhibits where people will walk through and go, “Oh wow, that’s powerful,” before being distracted by their phone (or AI brain implant?) reminding them it’s time to go pick up their kids. Is that the foundation of your purpose for photographing?

No, no, neither of those things. It’s something more immediate and gratifying.

To feel appreciated and have my perspective valued?

As you grow up and become more secure in yourself, you learn not to give credence to everyone's opinion and to be more selective with which voices you value. In short, you learn to stop looking for depth in shallow places. You learn that if you are satisfied with an image, that’s enough. It’s nice to have people whose taste I respect appreciate my work, and it’s an encouragement to continue, but it’s not why I do it.

What about to live a more fulfilling life?

Sure. As a photographer, I've been to many places, met many people, and had experiences that would never have happened otherwise. It’s made me less ignorant and more empathetic and given me confidence in who I am. The camera has permitted me to lean into my curiosity and become more. This feeling is certainly a driving force for the continuation of my work.

To inspire others to do the same so their life might be more fulfilling?

It sure is pretty to think so.

To understand myself and what I value?

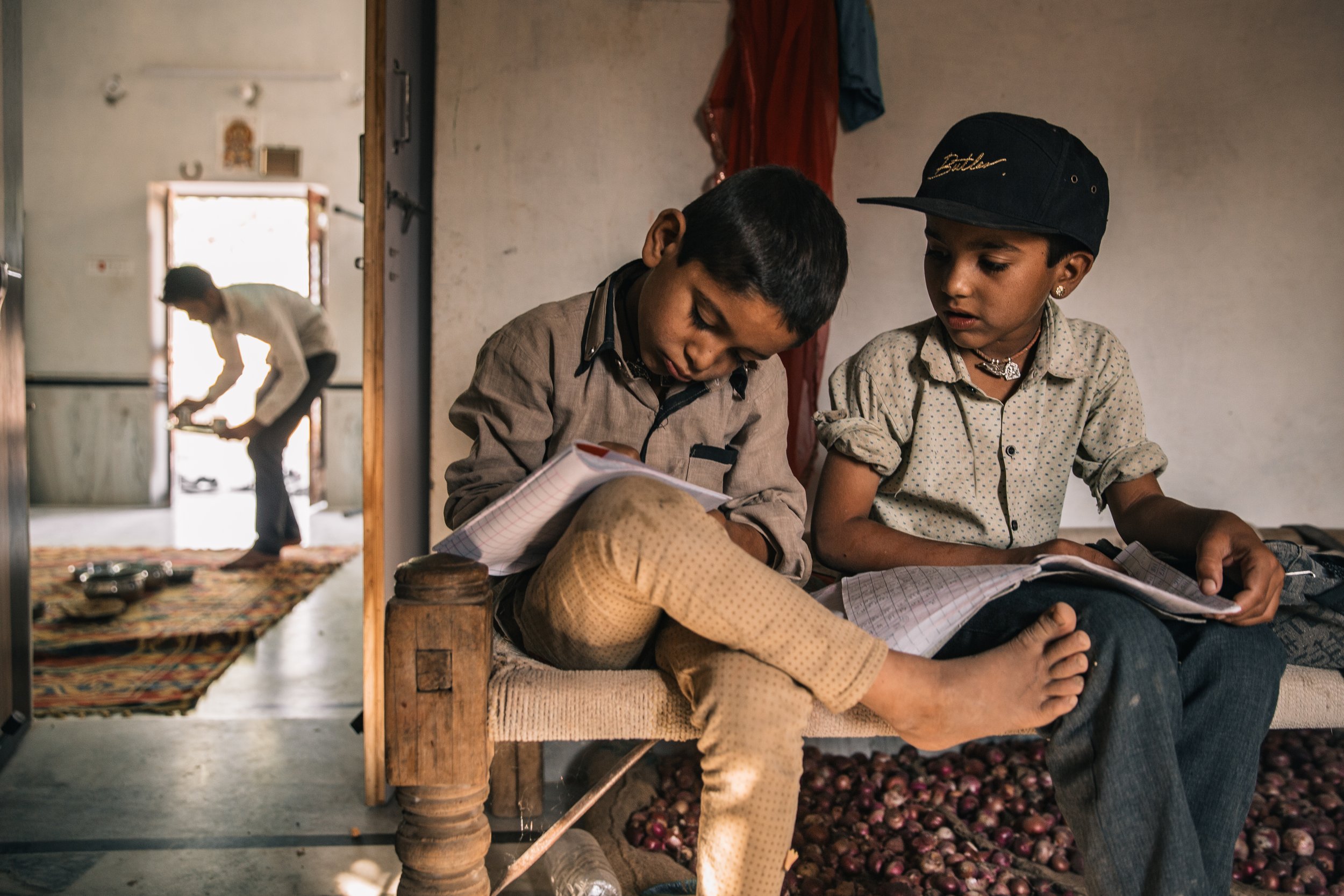

Most certainly. To make a photograph is to pick a moment out of the chaos of infinite others because you saw something valuable. To choose a splice of time and space and frame it through your perspective because it is inherently unique. Because you connected with it. To be aware. This almost always happens subconsciously and is intuited and felt instinctually rather than being overly considered and conscious. My taste, my soul itself, guides me, pulling my finger down at that precise moment.

Reviewing these moments can give me a deeper understanding of myself and what I find valuable. Over the years, these thousands of photographs begin to paint a picture of not just what I find valuable but also who I am in a broader sense, as they are the moments I’ve given my life to.

To communicate?

Another cliche is that photography is the universal language. This is, of course, true. Although the photographic interpretation of images can vary greatly across different cultures and contexts, and what resonates as powerful in one culture may be misinterpreted or overlooked in another, it is nonetheless a means of instant communication. It is as much an expression of ourselves as it is an expression of our world—a way to tell the story of our lives. We don’t just recognize these little moments as what we value but desire to present them to the world, hoping that those who see them might recognize a shared humanity and connection. That we both might feel less alone in our shared experience. We hope the moments we lived and experienced might call to the deepest part of others that wells up in gratitude for the opportunity to have been alive at all and mutual camaraderie in having been here in this place, in this time, together.

So, why photograph at all?

Ultimately, there are many reasons to make photographs, depending on the subject and photographers life, and I could write an entire book outlining them. However, the question of “Why photograph at all?” is less about making a list of every reason people photograph and more about understanding why I photograph and which reasons hold water. I would also be remiss if I did not mention that photography is a disease in some sense. A compulsion. A tick. Even when I want to relax and put the camera down, it is as if I asked myself to take a break from breathing, and always find myself gasping for air. This is because it has become tied to my purpose for existing. It is not a hobby or even a profession but a confession.

Happiness is progress towards a worthwhile goal. The goal of understanding myself and the world around me is worthwhile, and progress is inevitable so long as I can pick up a camera and walk out my front door. Therefore, it is not just a means of temporary, hedonistic, ‘small h’ happiness, but Happiness in a more profound sense, which I suppose you could call joy, and that joy is inherent in all of the lesser reasons I photograph too.